by Laura Schonberg

When my mare Poema first came home she had not been bridled, saddled, or ridden. I wanted to build on what I learned from developing working relationships with my first two horses and, in particular, avoid the mistake of going too far too fast.

I naturally operate with a “get r’ done” type of attitude. This is detrimental to all horses, but particularly to a wary green mustang. Starting with the simple, but not necessarily easy, process of having her be willing to meet me when I approach her was key. Does she turn, look and wait for me or walk away when she sees the halter? Does she stand when I get to her side? After getting to a place where haltering was easy we started working on bridling.

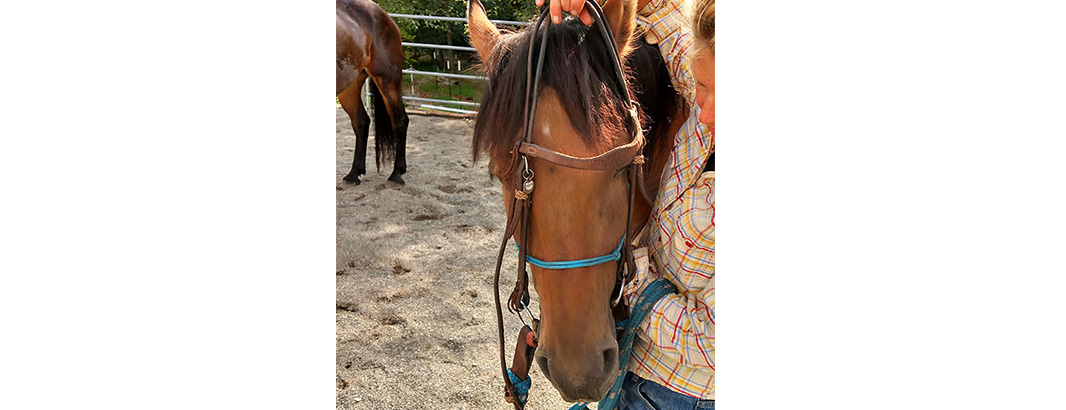

Bridling is something that I have had to revisit over and over in the last three months with Poema. If I rush, if I don’t recognize her mental state (other activities are a huge distraction and concern) and if she doesn’t feel like she’s safe, bridling can be frustrating and set a very negative tone for our interaction. As discussed last month, the same components for haltering a horse with “feeling” applies to bridling.

The wait: The first critical step is taking the time to establish a stand. This is something that can be practiced and perfected in small steps, all the time. A busy 40-something woman has a lot on her plate; I know I tend to easily get impatient with my horse. In order for bridling to be safe and efficient, Poema has to know how to stand, and stand quietly. If she needs to move her feet, hind, front, head, I want to respond quickly, with as little correction as it takes.

The stand: One of the key steps in haltering is that my green horse stands still. And not just stands, but stands quietly—without pushing into me, stepping away or on me, or throwing her head around. This also includes that she’s comfortable with my hands all over her, ears to tail and belly to feet. I take the time and go back to my ground work until the stand is something my horse seeks. While this might take away from riding, it allows us to be “together” during the bridling process. This translates to togetherness in the saddle.

The head: As in haltering, I want my horse to be feeling of/for me in positioning her head for bridling. This position shouldn’t be too high or too low. I also want the horse standing quietly, with a soft bend in her neck while staying balanced at her poll to the left. I always bridle with my right arm over her poll, holding the bridle in that hand, and wait for my horse to find the position. This can take a tremendous amount of time and patience; it’s important not to rush it. When I rush, it actually takes longer and I have to get bigger in my fixes. It is helpful to visualize exactly where I need the horse to be and make small fixes as soon as possible. With Poema, if she is impatient and distracted we will get her feet moving so the stand is a comfortable, quiet place that she seeks.

The bridle: Once Poema is standing with her head positioned as I need it, there is the quiet acceptance of the bit. This will happen when she is comfortable and accustomed to her ears being touched and her face being handled. Any one of the previous steps can be uncomfortable and/or a place of concern for the horse and may need to be broken down further and practiced in smaller steps. I also need to be very aware of where my reins are as there can be catastrophic situations when a horse or human gets caught up in the reins. Management of the halter lead and reins is a critical component of bridling safely.

Since bridling sets the tone of the entire ride, it is well worth addressing the small braces and impulsive energy a horse can have in the process, taking the time to be deliberate, focused and calm. On those nights where I don’t have the time to work with my horse in the saddle, practicing “getting dressed” for that ride is time well spent. Working on the components of bridling is better than doing nothing, and actually has tremendous pay-offs in the future.

Published in September 2015 Issue

Thankful to call the Pacific Northwest home, Laura Schonberg is an educator in a local school district and is outside at her place when she isn’t inside at work. Summers are spent cow-girling at a friend’s ranch, with forrays into the Cascade Mountains as time and weather permit year-round. Winter finds her at a local barn doing dressage lessons to support her ranch riding, and re-starting horses through the county’s equine rescue program.

I like how she points out that the horses attitude is important. Be very caution if your bridle by reaching over the poll. Please also be aware that even the best trained horses can unexpectedly raise their head in a direction that can damage your shoulder.