Part 2: Distracted by Talent?

By Laura Schonberg

I’m guilty: at a riding lesson a couple of weeks ago, I was watching with girl-who-loves-everything-horse awe as one of my trainers was riding her well-bred warmblood in the arena. This horse doesn’t move––she floats. If I didn’t know any better, I would swear this horse likes being collected, that her hooves never touch the ground, and that she loves the demands and repetition of moving under a rider. She makes 20-meter circles in any gait look easy and beautiful. It turns out I am easily distracted by equine talent.

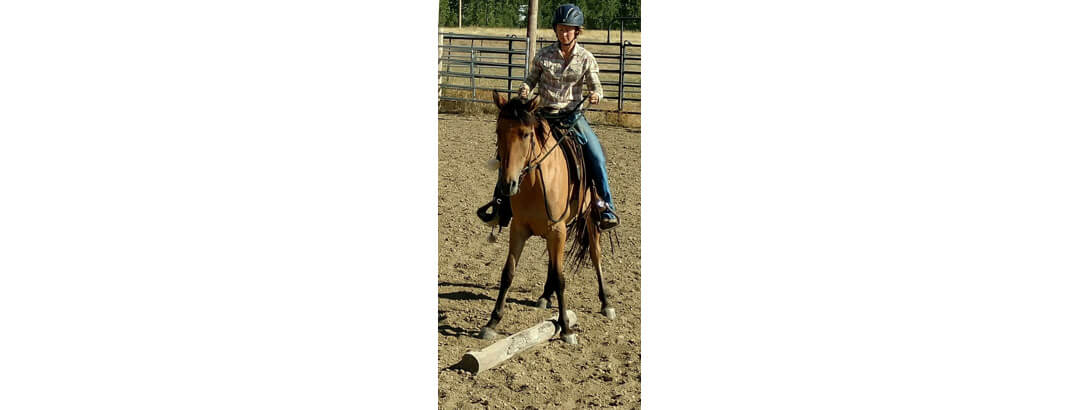

My own two riding horses are a 17-hand Percheron/Quarter horse, and what I tell people is a 14-hand mustang. I started both horses; all of their habits and quirks are mine to claim. They’re also both sort-of rejects. My draft cross was a “mistake” from up-river, and the mustang is, well, a mustang––a horse “bred” to live in the wild, which means there’s no particular breeding line at all.

I would say that we live up to our low-class standard in the horse world by being neither expensive nor cultivated. While we try lots of things (jumping, dressage, cow sorting, ranch work, obstacles, distance riding), we have no misguided hopes of greatness. I am particularly conscious of this when I am amongst talent: a cow horse that twitches an ear resulting in a calf going where it’s supposed to, or a jumper that is as fluid as water over a course. My hopes get dashed and my confidence gets shot.

There are undoubtedly talented horses and talented riders that we aspire to emulate. In doing so, it’s easy to write-off our own efforts with excuses of my horse isn’t papered, or this is all I could afford, or I don’t have time/money/energy/location/patience to take lessons. It’s much simpler to make an excuse or offer a valid reason for why I still get yelled at in the branding pen or why I struggle to have a collected canter. But aptitude doesn’t guarantee achievement. Talent is way different than excelling.

Talent in equine sports can result in points, ribbons, standings, and prize money. But what do we mean by “talent”? If we’re talking about true horsemanship, it’s not just intrinsic skills, it’s also the ability to learn and grow.

To develop talent in ourselves and our horses we need to ask a few questions: How can I struggle a bit longer and how can I find a different way to offer to my horse what I want? What is the importance of our effort? How can I sustain a positive attitude about getting out there day after day and have my horse want to keep working with me, seek me out, and not get dull?

A preoccupation with talent means that I am deliberately neglecting other aspects of training. Things like hard work, positive attitude, graciousness to others, balance in life, having fun, and learning from mistakes. It might also mean I’m choosing to deliberately not notice or remember things that I need to keep puzzling over: Why does he pin his ears when I ask for his left hind? Why does she brace her head when I ask for that lead? Why does my horse resist when I ask him to carry a soft feel? Why are things not shaping up the way I want them to? How can I ask my horse to give me her all when I don’t listen to what she’s telling me?

Equine sporting can mean focusing our measure of success on short-term performance, while discouraging our long-term learning and growth. As a person who tends to hide her competitive, type-A personality, I admit to a deep insecurity to showing off. It’s so easy in our culture to make winning the object of our relationship with the horse. It’s so easy for me to fall into a trap of insecurity when I’m around “real” cowboys working in a branding pen or when I ride in front of a Rolex competitor. By focusing on what is judged as “success” or talent, I am developing in my work-ethic a mentality that rewards hypocrisy with my horse and discourages integrity in my horsemanship.

My hope is that as a rider, I can find a way to raise the bar while raising my grit: be willing to learn, be hopeful and have a commitment to increasing my effort. Greatness does not come easily. And while my greatness might not look like Pegasus crossed with a unicorn who has cow sense, I can start and end each ride with my horse still happy to be with me. Then I know I’m on the right path.

Thankful to call the Pacific Northwest home, Laura Schonberg is an educator in a local school district and is outside at her place when she isn’t inside at work. Summers are spent cow-girling at a friend’s ranch, with forrays into the Cascade Mountains as time and weather permit year-round. Winter finds her at a local barn doing dressage lessons to support her ranch riding, and re-starting horses through the county’s equine rescue program.